Time once more for a multi-part interview, this time with Al Dempster, one of the pillars of the Disney b.g. department from the late thirties to the seventies.

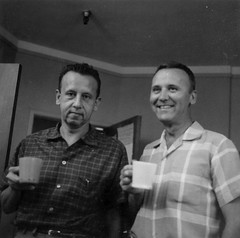

Albert Dempster -- seen here with layout artist Don Griffith (l) -- was a crackerjack background artist who worked on almost every Disney animated feature from Pinocchio to The Rescuers.

The following interview is lengthy, so it's broken into bite-sized pieces.

Interviewed by Christopher Finch and Linda Rosenkrantz on May 31, 1972.

If one were to invent a ratio between fame and quality of art created, the Disney background artists would probably appear lowest on the chart. While their art is key to the feelings animated movies generate—be they reassuring feelings like in Snow White or jazzy ones like in The Jungle Book—it is also at its best when absolutely non-obtrusive. No wonder then that aside from notable exceptions like Maurice Noble background artists are often forgotten by official histories of animation.

Albert T. Dempster worked as a background artist on virtually all of Disney animated features from Pinocchio to The Rescuers, where he was responsible for color styling. Throughout his career at the Studio, he also tackled quite a few shorts, including Canine Casanova (1945), Father’s Week-end (1953), Casey Bats Again (1954), A Cowboy Needs a Horse (1956), The Truth about Mother Goose (1957), and How to Have an Accident at Work (1959).

Born on July 23, 1911, Al joined the Disney Studio on March 6, 1939 in Layout and was transferred to the Background Department on June 27, 1939.

From November 1945 to January 1952 Al Dempster left Disney “to work on a ranch doing children’s book illustrations,” including over a dozen Disney Golden books. He returned to the Studio on January 7, 1952 and resumed working as a background artist until his retirement on July 31, 1973. He came out of retirement at the studio's behest to work on "The Rescuers", then finally called it a career.

Al Dempster passed away on June 28, 2001 in Ventura, CA

Christopher Finch: What we wanted to talk to you about was working here in general and working on backgrounds in particular and more specifically Robin Hood, because we'll be doing a section on the making of Robin Hood.

Al Dempster: Well, let's see, as far as the background aspects go, it's no different from other pictures. We have the same set of problems for every one, in that the characters are always the constant and we can't change the lighting on them in one scene. We try to keep them all the same color and value, so that they are consistent.

Then the backgrounds have to be consistent in the sequence, especially to follow through in dark and light and color too, so that there's no sudden drop-off in lighting. But they still have to read in quite a variety of settings, and against a variety of values which makes it a little difficult at times. Because of it we subordinate what we call the background, and it strictly becomes a background, a supporting thing for the action, to enhance the action and put it in a setting, to make it believable. That's what we do and we're the last people that handle it before it goes to camera.

CF: The animators work with the layouts?

AD: The animators work with the rough layouts, and after the rough layouts are proven with the animation in running black and white tests, the animation is cleaned up or whatever is necessary and the layouts are cleaned up. In Robin Hood, as in other pictures that we've done, like The Aristocats but not The Jungle Book, we use a Xerox line for backgrounds as the characters also do. We receive a cel print (which is called the CL) and we also get an illustration board with the cleaned-up layout, transferred in Xerox upon it.

Now this would be what a cleaned-up layout looks like and this is the blue sketch. Are you familiar with any of these?

CF: We’ve just seen some of them in the Morgue.

AD: Well, these blue sketches are just sort of a rough resume of the beginning and the end of an action that occurs in the scene, so it gives us an idea about scale and about who's going to be in the scene and where they're going to be and what type of rough action they're going to have.

CF: This is done in layout, is it?

AD: This is done either by layout from the animation drawings or it's traced from the drawings by someone specifically who does this sort of thing. Typical start and finish of action. So it's a guide, more or less, for us. And until we get the color models for each one of these scenes, we have a rough [idea of] how this scene must be painted to support it.

Now, this is the illustration board that we work on and this is what's known as the CL. Then the reason for this is, quite often after this is painted, the Xerox lines on the background are painted out and lost. You know we work with thin, wash-type poster color. It's a thin watercolor, some of it opaques out because of necessity when making changes here and there. So, with the CL over the background, we can replace those lines that are important and remove those that interfere with action or depth.

One might just want the lines only in the foreground where the characters who have the black lines will contact it. So, that's why we have the cel. And we can remove lines where we don't want them, to push it back, back in the distance. We can remove lines with a material that is like a solvent. So all the layouts are dished up like this for us.

Most are this size [10 ½” x 14 1/2”]. It is a 6 ½ field size. It is generally the format that we all work with. On occasion we have a special situation that will call for a larger size like the exterior of this church, or interior of the same church. Those are called 10 field.

The reason for that is the characters are small in the scene. Now if they were animated for a scale that would work on a 6 ½ field, they'd be infinitesimal, very difficult for the animator to work that way. So everything revolves around the convenience of the animator, because it's a very difficult thing to get these characters to move properly without the lines becoming huge when blown up on the screen. On rare occasions we've gone bigger than that, but only for an extremely special thing.

CF: Like with Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio you might have?

AD: I don't think we went any bigger than that. Except for one scene: the opening scene. The Blue Fairy, as she came across over the countryside and down over the village. That was a rather large one. Then occasionally on some of the space pictures we've done huge backgrounds: the camera can stay real close on a small field and then pull back to get the immensity of the space it's going into. The animation could be bi-packed, which is a way of doing the animation on one strip of film and the background on the other material that keeps its size. You get that on another strip of film and the two are put together in the printer.

These layouts seem very different and very much more schematic than some of the layouts we've seen for earlier films, for Pinocchio for example. Those were completely rendered and done in value, black and white, because the two men who were working on those… two or three layout guys liked to work on the values and it was sort of a growing business.

Now, I didn't come here until just after Snow White but the two men who I remember were the mainstays: Hugh Hennessey and Charles Philippi. There were others too, but they were the principle layout men and they enjoyed doing these full-value sketches. They were a great aid for keeping neophyte painters, as it were, (who didn't know a heck of a lot about painting) in line.

Consequently they had to have things pretty well spelled out for them. On Pinocchio, it was the same way. Quite a few of the layouts were done in very detailed value, and actually I don't think that hurt the picture at all: it had a certain richness because of it. It kept the mood of the picture pretty well under control, so that there'd be 12, 14 people on that picture, just two or three or four laying out, the picture was more consistent.

1 comments:

A big thank you for posting this interview.

It's gold dust for BG painters.

Post a Comment