As we roll toward Friday and the long, holiday weekend, a few observations about studios 'round and about...

Disney Toons Sonora starts second-floor renovations in a couple of weeks, renovations to occur nights and weekends. The initial work-space changes were, ahm, not loved by the artists who were going to be working there. To management's credit, they listened to the crew's suggestions and changed the layout and furniture ideas.

Over at Cartoon Network, "The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy" looks to be wrapping up its long production run in November and December. (This isn't 100%, but it appears likely.) Some artists are being laid off, other artists are swining onto other CN shows...

I found out yesterday that I'm a bad little business agent. While over at IDT Entertainment, I was informed that my blogging about the format of the upcoming "Simpsons" feature displeased some execs at Fox, who considered the info confidential and wanted to roll out the news themselves. So, to demonstrate that I am a straight-up guy who wants to make things right, I hereby apologize.

Click here to read entire post

As we roll toward Friday and the long, holiday weekend, a few observations about studios 'round and about...

Disney Toons Sonora starts second-floor renovations in a couple of weeks, renovations to occur nights and weekends. The initial work-space changes were, ahm, not loved by the artists who were going to be working there. To management's credit, they listened to the crew's suggestions and changed the layout and furniture ideas.

Over at Cartoon Network, "The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy" looks to be wrapping up its long production run in November and December. (This isn't 100%, but it appears likely.) Some artists are being laid off, other artists are swining onto other CN shows...

I found out yesterday that I'm a bad little business agent. While over at IDT Entertainment, I was informed that my blogging about the format of the upcoming "Simpsons" feature displeased some execs at Fox, who considered the info confidential and wanted to roll out the news themselves. So, to demonstrate that I am a straight-up guy who wants to make things right, I hereby apologize.

Click here to read entire post

Thursday, August 31, 2006

A Mid-Week Studio Roundup

As we roll toward Friday and the long, holiday weekend, a few observations about studios 'round and about...

Disney Toons Sonora starts second-floor renovations in a couple of weeks, renovations to occur nights and weekends. The initial work-space changes were, ahm, not loved by the artists who were going to be working there. To management's credit, they listened to the crew's suggestions and changed the layout and furniture ideas.

Over at Cartoon Network, "The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy" looks to be wrapping up its long production run in November and December. (This isn't 100%, but it appears likely.) Some artists are being laid off, other artists are swining onto other CN shows...

I found out yesterday that I'm a bad little business agent. While over at IDT Entertainment, I was informed that my blogging about the format of the upcoming "Simpsons" feature displeased some execs at Fox, who considered the info confidential and wanted to roll out the news themselves. So, to demonstrate that I am a straight-up guy who wants to make things right, I hereby apologize.

Click here to read entire post

As we roll toward Friday and the long, holiday weekend, a few observations about studios 'round and about...

Disney Toons Sonora starts second-floor renovations in a couple of weeks, renovations to occur nights and weekends. The initial work-space changes were, ahm, not loved by the artists who were going to be working there. To management's credit, they listened to the crew's suggestions and changed the layout and furniture ideas.

Over at Cartoon Network, "The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy" looks to be wrapping up its long production run in November and December. (This isn't 100%, but it appears likely.) Some artists are being laid off, other artists are swining onto other CN shows...

I found out yesterday that I'm a bad little business agent. While over at IDT Entertainment, I was informed that my blogging about the format of the upcoming "Simpsons" feature displeased some execs at Fox, who considered the info confidential and wanted to roll out the news themselves. So, to demonstrate that I am a straight-up guy who wants to make things right, I hereby apologize.

Click here to read entire post

Mornings on "Simpsons"

Yesterday I wandered the first-floor of IDT Entertainment, where "The Simpsons" feature is in full swing...

There's a lot more crew in the last few weeks, and many are into overtime hours (ten to fifteen extra hours per week). Artists told me they expect the schedule to get more challenging as they go along, since the July release date is set in concrete while the amount of work is piled high.

But morale is also high; everyone knows they're working on a quality product. One of the animators said: "I've seen the story reels a few times now, and they keep getting better and better. I've laughed more watching the reels of this picture than others that I've worked on..."

Click here to read entire post

Yesterday I wandered the first-floor of IDT Entertainment, where "The Simpsons" feature is in full swing...

There's a lot more crew in the last few weeks, and many are into overtime hours (ten to fifteen extra hours per week). Artists told me they expect the schedule to get more challenging as they go along, since the July release date is set in concrete while the amount of work is piled high.

But morale is also high; everyone knows they're working on a quality product. One of the animators said: "I've seen the story reels a few times now, and they keep getting better and better. I've laughed more watching the reels of this picture than others that I've worked on..."

Click here to read entire post

Whoops

As I said in one of the sections down below, we accidentally turned off "Comments" for a few days. It's fixed now. But please accept our apologies.

Click here to read entire post

As I said in one of the sections down below, we accidentally turned off "Comments" for a few days. It's fixed now. But please accept our apologies.

Click here to read entire post

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Remembering Tony Rivera

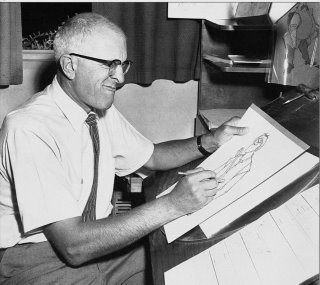

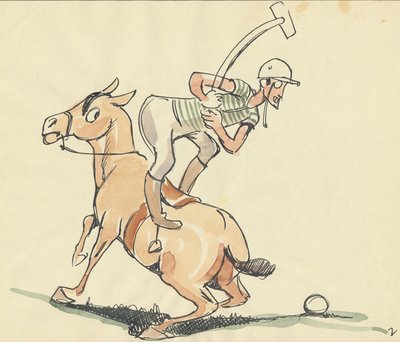

Below: Tony Rivera, by Bill Herwig, 1934.

Another animation veteran who often falls below the radar because he was, well, just a solid, dependable, no-nonsense animation artist who worked in the trenches and contributed to great art: Tony Rivera...

Tony came into the cartoon business in the middle thirties, worked at one of Grim Natwick's assistants on "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," walked out on strike at Disney's in 1941 and thereafter worked at almost every animation studio of note until his retirement half a century later. (Click on that link up above for tales of Tony on "Cartoon Diaries.")

When I knew Tony, he was doing layouts for Hanna-Barbera on "Yogi Bear" and "Quick Draw McGraw." I knew him not through my background-artist father, but through my mother, who dragged me to weekly piano lessons with Tony's wife Mary. Their Tujunga house sat high on the slopes of the Angeles Crest Mountains, and I have vivid memories of the long, vertical driveway, yucca plants, and the sharp odor of hardwood mesquite. (Then as now, lots of animation people lived in the uplands of the Crescenta-Canada valley, which encompasses Sunland-Tujunga, La Crescenta, and La Canada-Flintridge.)

I would almost always arrive early for my piano lesson (I was a ghastly student), and beeline for Tony's studio on the west end of their airy house. There I would watch Mr. Rivera draw layouts for the latest H-B short.

The studio was roaring then (this was 1960) and stuffed to the rafters. Tony, like many staff artists, worked at home, turning out the layouts for a "Quick Draw" or "Yogi" short every week. I would stand there, my 11-year-old mouth hanging open, and watch him draw -- the horizon line, trees, the curves and planes of Yogi and Boo-Boo in the foreground And he would talk to me about what he was doing, show me the storyboards from which he worked, and demonstrate the Lucy where he enlarged story panels. I remember it seemed a lot different than watching my father painting water colors in his studio.

And we're now further away from that time than Tony was from his beginnings at the Disney Hyperion studio in 1960. Scary.

Another animation veteran who often falls below the radar because he was, well, just a solid, dependable, no-nonsense animation artist who worked in the trenches and contributed to great art: Tony Rivera...

Tony came into the cartoon business in the middle thirties, worked at one of Grim Natwick's assistants on "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," walked out on strike at Disney's in 1941 and thereafter worked at almost every animation studio of note until his retirement half a century later. (Click on that link up above for tales of Tony on "Cartoon Diaries.")

When I knew Tony, he was doing layouts for Hanna-Barbera on "Yogi Bear" and "Quick Draw McGraw." I knew him not through my background-artist father, but through my mother, who dragged me to weekly piano lessons with Tony's wife Mary. Their Tujunga house sat high on the slopes of the Angeles Crest Mountains, and I have vivid memories of the long, vertical driveway, yucca plants, and the sharp odor of hardwood mesquite. (Then as now, lots of animation people lived in the uplands of the Crescenta-Canada valley, which encompasses Sunland-Tujunga, La Crescenta, and La Canada-Flintridge.)

I would almost always arrive early for my piano lesson (I was a ghastly student), and beeline for Tony's studio on the west end of their airy house. There I would watch Mr. Rivera draw layouts for the latest H-B short.

The studio was roaring then (this was 1960) and stuffed to the rafters. Tony, like many staff artists, worked at home, turning out the layouts for a "Quick Draw" or "Yogi" short every week. I would stand there, my 11-year-old mouth hanging open, and watch him draw -- the horizon line, trees, the curves and planes of Yogi and Boo-Boo in the foreground And he would talk to me about what he was doing, show me the storyboards from which he worked, and demonstrate the Lucy where he enlarged story panels. I remember it seemed a lot different than watching my father painting water colors in his studio.

And we're now further away from that time than Tony was from his beginnings at the Disney Hyperion studio in 1960. Scary.

Below: In 1985 (a year before his death), Tony Rivera accepts the Golden Award from Local 839 Business Representative Bud Hester.

Click here to read entire post

Click here to read entire post

Starz in Animation

A top-of-the-fold, front-page story from today's VARIETY tells a tale that has an impact on animation artists. (This version isn't exactly VARIETY's, but since the trade rag hides behind a subscription site, it will suffice...)

Starz Media, as we've said here before, is picking up IDT Entertainment and its related companies from IDT (the telephone communications company). From VARIETY:

A top-of-the-fold, front-page story from today's VARIETY tells a tale that has an impact on animation artists. (This version isn't exactly VARIETY's, but since the trade rag hides behind a subscription site, it will suffice...)

Starz Media, as we've said here before, is picking up IDT Entertainment and its related companies from IDT (the telephone communications company). From VARIETY:

...Twentieth Century Fox will distribute four full-length animated reatures from IDT Entertainment under a deal concluded before John Malone's Liberty Media bought IDT. Twentieth has an output deal with HBO, which gets first refusal on those animated theatricals (although a clause in its contract allows HBO to pass on animated product)...Word circulates that Liberty/Starz is more interested in the live-action component of their new businesses than the animation. (But hey. They have a lot of "Simpsons" working going on, don't they?) Whether a lack of ardor for cartoons impacts the size and shape of animation staff in the coming year is anyone's guess. IDT Entertainment's first theatrical animated release "Everyone's Hero" arrives in theatres this Fall. The new company will probably analyze how it performs and decide if it wants to stay heavily invested in the animated feature business. Click here to read entire post

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Dancing To and From...and To...Disney Feature Animation

Right: Another Degas study from Virgil Partch's Disney traffic boy period; February 1938.

Multiple trips to Disney Feature Animation for Yours Truly, one on Monday, and one with the IA Rep today. What's obvious: everybody on "Meet the Robinsons" is going at high revs... "Robinsons" layout staff finished most of its heavy overtime last week. "Robinsons" animators still have pedal to the metal, and the finaling department -- down on the first floor -- still has months of work ahead of it... There continues to be some nervousness about the end of Personal Service Contracts. A number of Disneyites are now being carried on overhead charge numbers (instead of production charge numbers) while their productions are re-worked in story. As a result, some staffers have shorter hours (11 a.m. to 5 p.m.) and minimal workloads. They're being carried now, but as one of them mentioned: "What if the company decides to put some of us on four-month layoff? There's no Personal Service Contracts to backstop us anymore." Nervousness on this count will probably dissipate when the development/production pipleline gets unkinked, and employees swing from the end of one show onto the start of another. Shorts: As we've said before, Lasseter and Catmull want to put a bunch of new animated shorts into production, the idea being that a new one* will be up in front of each new animated feature as it lifts off at the box office. The thought originally was (we're told) to get a new one produced for "Meet the Robinsons," but its release schedule is too tight for that to happen. So, a Golden Oldie will be dusted off for "Robinsons," and new one-reelers created for the animated features sitting further down the tarmac ("American Dog," "Joe Jump," "Rapunzel," etc.) *As at Pixar, ideas for shorts are pitched to a "brain trust" of Disney directors and story supervisors. One storyman related: "Execs sometime sit in, but it's the directors and story leads making the decisions." Click here to read entire postThe Risk Pool

Over the weekend, Kevin Koch raved to me about an article in The New Yorker entitled "The Risk Pool," written by the author of The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell.

At almost the same time, an animation guild member e-mailed me the piece (great minds think alike). Because there's no link at the New Yorker website, we post the entire article below. It's worth looking at, because it explains the reasons so many pension plans are going down the drain today...

Over the weekend, Kevin Koch raved to me about an article in The New Yorker entitled "The Risk Pool," written by the author of The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell.

At almost the same time, an animation guild member e-mailed me the piece (great minds think alike). Because there's no link at the New Yorker website, we post the entire article below. It's worth looking at, because it explains the reasons so many pension plans are going down the drain today...

THE RISK POOL, by MALCOLM GLADWELL The years just after the Second World War were a time of great industrial upheaval in the United States. Strikes were commonplace. Workers moved from one company to another. Runaway inflation was eroding the value of wages. In the uncertain nineteen-forties, in the wake of the Depression and the war, workers wanted security, and in 1949 the head of the Toledo, Ohio, local of the United Auto Workers, Richard Gosser, came up with a proposal. The workers of Toledo needed pensions. But, he said, the pension plan should be regional, spread across the many small auto-parts makers, electrical-appliance manufacturers, and plastics shops in the Toledo area. That way, if workers switched jobs they could take their pension credits with them, and if a company went bankrupt its workers’ retirement would be safe. Every company in the area, Gosser proposed, should pay ten cents an hour, per worker, into a centralized fund. The business owners of Toledo reacted immediately. “They were terrified,” says Jennifer Klein, a labor historian at Yale University, who has written about the Toledo case. “They organized a trade association to stop the plan. In the business press, they actually said, ‘This idea might be efficient and rational. But it’s too dangerous.’ Some of the larger employers stepped forward and said, ‘We’ll offer you a company pension. Forget about that whole other idea.’ They took on the costs of setting up an individual company pension, at great expense, in order to head off what they saw as too much organized power for workers in the region.” A year later, the same issue came up in Detroit. The president of General Motors at the time was Charles E. Wilson, known as Engine Charlie. Wilson was one of the highest-paid corporate executives in America, earning $586,100 (and paying, incidentally, $430,350 in taxes). He was in contract talks with Walter Reuther, the national president of the U.A.W. The two men had already agreed on a cost-of-living allowance. Now Wilson went one step further, and, for the first time, offered every G.M. employee health-care benefits and a pension. Reuther had his doubts. He lived in a northwest Detroit bungalow, and drove a 1940 Chevrolet. His salary was ten thousand dollars a year. He was the son of a Debsian Socialist, worked for the Socialist Party during his college days, and went to the Soviet Union in the nineteen-thirties to teach peasants how to be auto machinists. His inclination was to fight for changes that benefitted every worker, not just those lucky enough to be employed by General Motors. In the nineteen-thirties, unions had launched a number of health-care plans, many of which cut across individual company and industry lines. In the nineteen-forties, they argued for expanding Social Security. In 1945, when President Truman first proposed national health insurance, they cheered. In 1947, when Ford offered its workers a pension, the union voted it down. The labor movement believed that the safest and most efficient way to provide insurance against ill health or old age was to spread the costs and risks of benefits over the biggest and most diverse group possible. Walter Reuther, as Nelson Lichtenstein argues in his definitive biography, believed that risk ought to be broadly collectivized. Charlie Wilson, on the other hand, felt the way the business leaders of Toledo did: that collectivization was a threat to the free market and to the autonomy of business owners. In his view, companies themselves ought to assume the risks of providing insurance. America’s private pension system is now in crisis. Over the past few years, American taxpayers have been put at risk of assuming tens of billions of dollars of pension liabilities from once profitable companies. Hundreds of thousands of retired steelworkers and airline employees have seen health-care benefits that were promised to them by their employers vanish. General Motors, the country’s largest automaker, is between forty and fifty billion dollars behind in the money it needs to fulfill its health-care and pension promises. This crisis is sometimes portrayed as the result of corporate America’s excessive generosity in making promises to its workers. But when it comes to retirement, health, disability, and unemployment benefits there is nothing exceptional about the United States: it is average among industrialized countries—more generous than Australia, Canada, Ireland, and Italy, just behind Finland and the United Kingdom, and on a par with the Netherlands and Denmark. The difference is that in most countries the government, or large groups of companies, provides pensions and health insurance. The United States, by contrast, has over the past fifty years followed the lead of Charlie Wilson and the bosses of Toledo and made individual companies responsible for the care of their retirees. It is this fact, as much as any other, that explains the current crisis. In 1950, Charlie Wilson was wrong, and Walter Reuther was right. The key to understanding the pension business is something called the “dependency ratio,” and dependency ratios are best understood in the context of countries. In the past two decades, for instance, Ireland has gone from being one of the most economically backward countries in Western Europe to being one of the strongest: its growth rate has been roughly double that of the rest of Europe. There is no shortage of conventional explanations. Ireland joined the European Union. It opened up its markets. It invested well in education and economic infrastructure. It’s a politically stable country with a sophisticated, mobile workforce. But, as the Harvard economists David Bloom and David Canning suggest in their study of the “Celtic Tiger,” of greater importance may have been a singular demographic fact. In 1979, restrictions on contraception that had been in place since Ireland’s founding were lifted, and the birth rate began to fall. In 1970, the average Irishwoman had 3.9 children. By the mid-nineteen-nineties, that number was less than two. As a result, when the Irish children born in the nineteen-sixties hit the workforce, there weren’t a lot of children in the generation just behind them. Ireland was suddenly free of the enormous social cost of supporting and educating and caring for a large dependent population. It was like a family of four in which, all of a sudden, the elder child is old enough to take care of her little brother and the mother can rejoin the workforce. Overnight, that family doubles its number of breadwinners and becomes much better off. This relation between the number of people who aren’t of working age and the number of people who are is captured in the dependency ratio. In Ireland during the sixties, when contraception was illegal, there were ten people who were too old or too young to work for every fourteen people in a position to earn a paycheck. That meant that the country was spending a large percentage of its resources on caring for the young and the old. Last year, Ireland’s dependency ratio hit an all-time low: for every ten dependents, it had twenty-two people of working age. That change coincides precisely with the country’s extraordinary economic surge. Demographers estimate that declines in dependency ratios are responsible for about a third of the East Asian economic miracle of the postwar era; this is a part of the world that, in the course of twenty-five years, saw its dependency ratio decline thirty-five per cent. Dependency ratios may also help answer the much-debated question of whether India or China has a brighter economic future. Right now, China is in the midst of what Joseph Chamie, the former director of the United Nations’ population division, calls the “sweet spot.” In the nineteen-sixties, China brought down its birth rate dramatically; those children are now grown up and in the workforce, and there is no similarly sized class of dependents behind them. India, on the other hand, reduced its birth rate much more slowly and has yet to hit the sweet spot. Its best years are ahead. The logic of dependency ratios, of course, works equally powerfully in reverse. If your economy benefits by having a big bulge of working-age people, then your economy will have a harder time of it when that bulge generation retires, and there are relatively few workers to take their place. For China, the next few decades will be more difficult. “China will peak with a 1-to-2.6 dependency ratio between 2010 and 2015,” Bloom says. “But then it’s back to a little over 1-to-1.5 by 2050. That’s a pretty dramatic change. Thirty per cent of the Chinese population will be over sixty by 2050. That’s four hundred and thirty-two million people.” Demographers sometimes say that China is in a race to get rich before it gets old. Economists have long paid attention to population growth, making the argument that the number of people in a country is either a good thing (spurring innovation) or a bad thing (depleting scarce resources). But an analysis of dependency ratios tells us that what’s critical is not just the growth of a population but its structure. “The introduction of demographics has reduced the need for the argument that there was something exceptional about East Asia or idiosyncratic to Africa,” Bloom and Canning write, in their study of the Irish economic miracle. “Once age-structure dynamics are introduced into an economic growth model, these regions are much closer to obeying common principles of economic growth.” This is an important point. People have talked endlessly of Africa’s political and social and economic shortcomings and simultaneously of some magical cultural ingredient possessed by South Korea and Japan and Taiwan that has brought them success. But the truth is that sub-Saharan Africa has been mired in a debilitating 1-to-1 ratio for decades, and that proportion of dependency would frustrate and complicate economic development anywhere. Asia, meanwhile, has seen its demographic load lighten overwhelmingly in the past thirty years. Getting to a 1-to-2.5 ratio doesn’t make economic success inevitable. But, given a reasonably functional economic and political infrastructure, it certainly makes it a lot easier. This demographic logic also applies to companies, since any employer that offers pensions and benefits to its employees has to deal with the consequences of its nonworker-to-worker ratio, just as a country does. An employer that promised, back in the nineteen-fifties, to pay for its employees’ health care when they were retired didn’t set aside the money for that while they were working. It just paid the bills as they came in: money generated by current workers was used to pay for the costs of taking care of past workers. Pensions worked roughly the same way. On the day a company set up a pension plan, it was immediately on the hook for all the years of service accumulated by employees up to that point: the worker who was sixty-four when the pension was started got a pension when he retired at sixty-five, even though he had been in the system only a year. That debt is called a “past service” obligation, and in some cases in the nineteen-forties and fifties the past-service obligations facing employers were huge. At Ford, the amount reportedly came to two hundred million dollars, or just under three thousand dollars per employee. At Bethlehem Steel, it came to four thousand dollars per worker. Companies were required to put aside a little extra money every year to make up for that debt, with the hope of someday—twenty or thirty years down the line—becoming fully funded. In practice, though, that was difficult. Suppose that a company agrees to give its workers a pension of fifty dollars a month for every year of service. Several years later, after a round of contract negotiations, that multiple is raised to sixty dollars a month. That increase applies retroactively: now that company has a brand-new past-service obligation equal to another ten dollars for every month served by its wage employees. Or suppose the stock market goes into decline or interest rates fall, and the company discovers that its pension plan has less money than it had expected. Now it’s behind again: it has to go back to using the money generated by current workers in order to take care of the costs of past workers. “You start off in the hole,” Steven Sass, a pension expert at Boston College, says. “And the problem in these plans is that it’s very difficult to dig your way out.” Charlie Wilson’s promise to his workers, then, contained an audacious assumption about G.M.’s dependency ratio: that the company would always have enough active workers to cover the costs of its retired workers—that it would always be like Ireland, and never like sub-Saharan Africa. Wilson’s promise, in other words, was actually a gamble. Is it any wonder that the prospect of private pensions made people like Walter Reuther so nervous? The most influential management theorist of the twentieth century was Peter Drucker, who, in 1950, wrote an extraordinarily prescient article for Harper’s entitled “The Mirage of Pensions.” It ought to be reprinted for every steelworker, airline mechanic, and autoworker who is worried about his retirement. Drucker simply couldn’t see how the pension plans on the table at companies like G.M. could ever work. “For such a plan to give real security, the financial strength of the company and its economic success must be reasonably secure for the next forty years,” Drucker wrote. “But is there any one company or any one industry whose future can be predicted with certainty for even ten years ahead?” He concluded, “The recent pension plans thus offer no more security against the big bad wolf of old age than the little piggy’s house of straw.” In the mid-nineteen-fifties, the largest steel mill in the world was at Sparrows Point, just east of Baltimore, on the Chesapeake Bay. It was owned by Bethlehem Steel, one of the nation’s grandest industrial enterprises. The steel for the Golden Gate Bridge came from Sparrows Point, as did the cables for the George Washington Bridge, and the materials for countless guns and planes and ships that helped win both world wars. Sparrows Point, a so-called integrated mill, used a method of making steel that dated back to the nineteenth century. Coke and iron, the raw materials, were combined in a blast furnace to make liquid pig iron. The pig iron was poured into a vast oven, known as an open-hearth furnace, to make molten steel. The steel was poured into pots to make ingots. The ingots were cooled, reheated, and fed into a half-mile-long rolling mill and turned into semi-finished shapes, which eventually became girders for the construction industry or wafer-thin sheets for beer cans or galvanized panels for the automobile industry. Open-hearth steelmaking was expensive and time-consuming. It required great amounts of energy, water, and space. Sparrows Point stretched four miles from one end to the other. Most important, it required lots and lots of people. Sparrows Point, at its height, employed tens of thousands of them. As Mark Reutter demonstrates in “Making Steel,” his comprehensive history of Sparrows Point, it was not just a steel mill. It was a city. In 1956, Eugene Grace, the head of Bethlehem Steel, was the country’s best- paid executive. Eleven of the country’s eighteen top-earning executives that year, in fact, worked for Bethlehem Steel. In 1955, when the American Iron and Steel Institute had its annual meeting, at the Waldorf-Astoria, in New York, the No. 2 at Bethlehem Steel, Arthur Homer, made a bold forecast: domestic demand for steel, he said, would increase by fifty per cent over the next fifteen years. “As someone has said, the American people are wanters,” he told the audience of twelve hundred industry executives. “Their wants are going to require a great deal of steel.” But Big Steel didn’t get bigger. It got smaller. Imports began to take a larger and larger share of the American steel market. The growing use of aluminum, concrete, and plastic cut deeply into the demand for steel. And the steelmaking process changed. Instead of laboriously making steel from scratch, with coke and iron ore, factories increasingly just melted down scrap metal. The open-hearth furnace was replaced with the basic oxygen furnace, which could make the same amount of steel in about a tenth of the time. Steelmakers switched to continuous casting, which meant that you skipped the ingot phase altogether and poured your steel products directly out of the furnace. As a result, steelmakers like Bethlehem were no longer hiring young workers to replace the people who retired. They were laying people off by the thousands. But every time they laid off another employee they turned a money-making steelworker into a money-losing retiree—and their dependency ratio got a little worse. According to Reutter, Bethlehem had a hundred and sixty-four thousand workers in 1957. By the mid-to-late-nineteen-eighties, it was down to thirty-five thousand workers, and employment at Sparrows Point had fallen to seventy-nine hundred. In 2001, Bethlehem, just shy of its hundredth birthday, declared bankruptcy. It had twelve thousand active employees and ninety thousand retirees and their spouses drawing benefits. It had reached what might be a record-setting dependency ratio of 7.5 pensioners for every worker. What happened to Bethlehem, of course, is what happened throughout American industry in the postwar period. Technology led to great advances in productivity, so that when the bulge of workers hired in the middle of the century retired and began drawing pensions, there was no one replacing them in the workforce. General Motors today makes more cars and trucks than it did in the early nineteen-sixties, but it does so with about a third of the employees. In 1962, G.M. had four hundred and sixty-four thousand U.S. employees and was paying benefits to forty thousand retirees and their spouses, for a dependency ratio of one pensioner to 11.6 employees. Last year, it had a hundred and forty-one thousand workers and paid benefits to four hundred and fifty-three thousand retirees, for a dependency ratio of 3.2 to 1. Looking at General Motors and the old-line steel companies in demographic terms substantially changes the way we understand their problems. It is a commonplace assumption, for instance, that they were undone by overly generous union contracts. But, when dependency ratios start getting up into the 3-to-1 to 7-to-1 range, the issue is not so much what you are paying each dependent as how many dependents you are paying. “There is this notion that there is a Cadillac being provided to all these retirees,” Ron Bloom, a senior official at the United Steelworkers, says. “It’s not true. The truth is seventy-five-year-old widows living on less than three hundred dollars to four hundred dollars a month. It’s just that there’s a lot of them.” A second common assumption is that fading industrial giants like G.M. and Bethlehem are victims of their own managerial incompetence. In various ways, they undoubtedly are. But, with respect to the staggering burden of benefit obligations, what got them in trouble isn’t what they did wrong; it is what they did right. They got in trouble in the nineteen-nineties because they were around in the nineteen-fifties—and survived to pay for the retirement of the workers they hired forty years ago. They got in trouble because they innovated, and became more efficient in their use of labor. “We are making as much steel as we made thirty years ago with twenty-five per cent of the workforce,” Michael Locker, a steel-industry consultant, says. “And it is a much higher quality of steel, too. There is simply no comparison. That change recasts the industry and it recasts the workforce. You get this enormous bulge. It’s abnormal. It’s not predicted, and it’s not funded. Is that the fault of the steelworkers? Is that the fault of the companies?” Here, surely, is the absurdity of a system in which individual employers are responsible for providing their own employee benefits. It penalizes companies for doing what they ought to do. General Motors, by American standards, has an old workforce: its average worker is much older than, say, the average worker at Google. That has an immediate effect: health-care costs are a linear function of age. The average cost of health insurance for an employee between the ages of thirty-five and thirty-nine is $3,759 a year, and for someone between the ages of sixty and sixty-four it is $7,622. This goes a long way toward explaining why G.M. has an estimated sixty-two billion dollars in health-care liabilities. The current arrangement discourages employers from hiring or retaining older workers. But don’t we want companies to retain older workers—to hire on the basis of ability and not age? In fact, a system in which companies shoulder their own benefits is ultimately a system that penalizes companies for offering any benefits at all. Many employers have simply decided to let their workers fend for themselves. Given what has so publicly and disastrously happened to companies like General Motors, can you blame them? Or consider the continuous round of discounts and rebates that General Motors—a company that lost $8.6 billion last year—has been offering to customers. If you bought a Chevy Tahoe this summer, G.M. would give you zero-per-cent financing, or six thousand dollars cash back. Surely, if you are losing money on every car you sell, as G.M. is, cutting car prices still further in order to boost sales doesn’t make any sense. It’s like the old Borsht-belt joke about the haberdasher who lost money on every hat he made but figured he’d make up the difference on volume. The economically rational thing for G.M. to do would be to restructure, and sell fewer cars at a higher profit margin—and that’s what G.M. tried to do this summer, announcing plans to shutter plants and buy out the contracts of thirty-five thousand workers. But buyouts, which turn active workers into pensioners, only worsen the company’s dependency ratio. Last year, G.M. covered the costs of its four hundred and fifty-three thousand retirees and their dependents with the revenue from 4.5 million cars and trucks. How is G.M. better off covering the costs of four hundred and eighty-eighty thousand dependents with the revenue from, say, 4.2 million cars and trucks? This is the impossible predicament facing the company’s C.E.O., Rick Wagoner. Demographic logic requires him to sell more cars and hire more workers; financial logic requires him to sell fewer cars and hire fewer workers. Under the circumstances, one of the great mysteries of contemporary American politics is why Wagoner isn’t the nation’s leading proponent of universal health care and expanded social welfare. That’s the only way out of G.M.’s dilemma. But, from Wagoner’s reticence on the issue, you’d think that it was still 1950, or that Wagoner believes he’s the Prime Minister of Ireland. “One thing I’ve learned is that corporate America has got much more class solidarity than we do—meaning union people,” the U.S.W.’s Ron Bloom says. “They really are afraid of getting thrown out of their country clubs, even though their objective ought to be maximizing value for their shareholders.” David Bloom, the Harvard economist, once did a calculation in which he combined the dependency ratios of Africa and Western Europe. He found that they fit together almost perfectly; that is, Africa has plenty of young people and not a lot of older people and Western Europe has plenty of old people and not a lot of young people, and if you combine the two you have an even distribution of old and young. “It makes you think that if there is more international migration, that could smooth things out,” Bloom said. Of course, you can’t take the populations of different countries and different cultures and simply merge them, no matter how much demographic sense that might make. But you can do that with companies within an economy. If the retiree obligations of Bethlehem Steel had been pooled with those of the much younger industries that supplanted steel—aluminum, say, or plastic—Bethlehem Steel might have made it. If you combined the obligations of G.M., with its four hundred and fifty-three thousand retirees, and the American manufacturing operations of Toyota, with a mere two hundred and fifty-eight retirees, Toyota could help G.M. shoulder its burden, and thirty or forty years from now—when those G.M. retirees are dead and Toyota’s now youthful workforce has turned gray—G.M. could return the favor. For that matter, if you pooled the obligations of every employer in the country, no company would go bankrupt just because it happened to employ older people, or it happened to have been around for a while, or it happened to have made the transformation from open-hearth furnaces and ingot-making to basic oxygen furnaces and continuous casting. This is what Walter Reuther and the other union heads understood more than fifty years ago: that in the free-market system it makes little sense for the burdens of insurance to be borne by one company. If the risks of providing for health care and old-age pensions are shared by all of us, then companies can succeed or fail based on what they do and not on the number of their retirees. When Bethlehem Steel filed for bankruptcy, it owed about four billion dollars to its pension plan, and had another three billion dollars in unmet health-care obligations. Two years later, in 2003, the pension fund was terminated and handed over to the federal government’s Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. The assets of the company—Sparrows Point and a handful of other steel mills in the Midwest—were sold to the New York-based investor Wilbur Ross. Ross acted quickly. He set up a small trust fund to help defray Bethlehem’s unmet retiree health-care costs, cut a deal with the union to streamline work rules, put in place a new 401(k) savings plan—and then started over. The new Bethlehem Steel had a dependency ratio of 0 to 1. Within about six months, it was profitable. The main problem with the American steel business wasn’t the steel business, Ross showed. It was all the things that had nothing to do with the steel business. Not long ago, Ross sat in his sparse midtown office and explained what he had learned from his rescue of Bethlehem. Ross is in his sixties, a Yale- and Harvard-educated patrician with small rectangular glasses and impeccable manners. Outside his office, by the elevator, was a large sculpture of a bull, papered over from head to hoof with stock tables. “When we showed up to the Bethlehem board to approve the deal, they had an army of people there,” Ross said. “The whole board was there, the whole senior management was there, people from Credit Suisse and Greenhill were there. They must have had about fifty or sixty people there for a deal that was already done. So my partner and I—just the two of us—show up, and they say, ‘Well, we should wait for the rest of your team.’ And we said, ‘There is no rest of the team, there is just the two of us.’ It said the whole thing right there.” Ross isn’t a fan of old-style pensions, because they make it impossible to run a company efficiently. “When a company gets in trouble and restructures,” he said, those underfunded pension funds “will eat it alive.” And how much sense does employer-provided health insurance make? Bethlehem made promises to its employees, years ago, to give them medical insurance in exchange for their labor, and when the company ran into trouble those promises simply evaporated. “Every country against which we compete has universal health care,” he said. “That means we probably face a fifteen-per-cent cost disadvantage versus foreigners for no other reason than historical accident. . . . The randomness of our system is just not going to work.” This is what Walter Reuther believed. He went along with Wilson’s scheme in 1950 because he thought that agreeing with Wilson was the surest way of getting Wilson and the other captains of industry to agree with him. “Reuther and his brain trust had a theory of capitalism,” Nelson Lichtenstein, the Reuther biographer, says. “It was: If we force G.M. to pay extra, we can create an incentive for G.M. to join our side.” Reuther believed, in other words, that when American corporations reached the point where they couldn’t make their business more efficient without making it less profitable, when their dependency ratios soared to unimaginable heights, when they got tens of billions behind in their health-care obligations, when the cost of carrying thou-sands of retirees forced them to stare bankruptcy in the face, they would come around to the idea that the markets work best when the burdens of benefits are broadly shared. It has taken half a century, but the world may finally be catching up with Walter Reuther.Click here to read entire post

Monday, August 28, 2006

Running Hard to Stay in Place

In the 1970s, the IATSE and other labor unions negotiated big percentage raises in minimum-rate wages. They sort of had to, since inflation was chewing up everybody's standard of living.

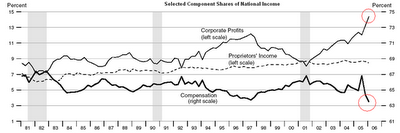

Now here we are, thirty-plus years later, and the IA (along with other unions and guilds) has negotiated 3 or 3 1/2 percent wage increases over the last couple of contract cycles. Trouble is, it isn't enough to keep pace with actual, real-world inflation. (4-6% anyone?) This article from today's New York Times gives some unsettling statistics...

Per the TIMES:

...Wages and salaries now make up the lowest share of the nation's gross domestic product since the government began recording the data in 1947, while corporate profits have climbed to their highest share since the 1960's. UBS, the investment bank, recently described the current period as "“the golden era of profitability."

Until the last year, stagnating wages were somewhat offset by the rising value of benefits, especially health insurance, which caused overall compensation for most Americans to continue increasing. Since last summer, however, the value of workers' benefits has also failed to keep pace with inflation, according to government data...

The entertainment biz, of course, is somewhat better off than other economic segments of the U.S.A., but we also take our hits. I remember when wages were sky-high in animation ten years ago. The good times, sadly, don't roll at the same velocity in 2006.

Click here to read entire post

In the 1970s, the IATSE and other labor unions negotiated big percentage raises in minimum-rate wages. They sort of had to, since inflation was chewing up everybody's standard of living.

Now here we are, thirty-plus years later, and the IA (along with other unions and guilds) has negotiated 3 or 3 1/2 percent wage increases over the last couple of contract cycles. Trouble is, it isn't enough to keep pace with actual, real-world inflation. (4-6% anyone?) This article from today's New York Times gives some unsettling statistics...

Per the TIMES:

...Wages and salaries now make up the lowest share of the nation's gross domestic product since the government began recording the data in 1947, while corporate profits have climbed to their highest share since the 1960's. UBS, the investment bank, recently described the current period as "“the golden era of profitability."

Until the last year, stagnating wages were somewhat offset by the rising value of benefits, especially health insurance, which caused overall compensation for most Americans to continue increasing. Since last summer, however, the value of workers' benefits has also failed to keep pace with inflation, according to government data...

The entertainment biz, of course, is somewhat better off than other economic segments of the U.S.A., but we also take our hits. I remember when wages were sky-high in animation ten years ago. The good times, sadly, don't roll at the same velocity in 2006.

Click here to read entire post

A Disney non-rejection letter

Light-years away from this one, but interesting nevertheless.

Light-years away from this one, but interesting nevertheless.

January 3rd, 1931.

Mr. Grimm [sic] Natwick c/o Ted Sears Room 56, 160 W. 45th St. New York, N. Y. Dear Grimm: Walt finally caught up with one of your pictures, and after our talking it over together, he has asked me to write to you. Frankly, Walt feels that your work, as he saw it, would not justify us in paying you the money that you seemed to feel you should have, when we talked in New York. However, he also feels that you have the makings and the background of a top-notch animator, and feels that if you are willing to co-operate to us to an extent, he would be very glad to have you come out. We would be willing to give you a contract for one year, at $150.00 per week for the first six months, and $175.00 per week for the last six months; we to have an option on your services for the following year at $200.00 per week. If you feel willing to accept this proposition, we will be glad to have ytou come out as soon as you can. Your reply to this letter can let this serve as a memorandum of agreement between us, and a contract can be dran up upon your arrival out here. We will of course pay your transportation out here. There is another angle to the work in connection with our studio, which you might consider, since, while it is nothing specific or concrete in the way of a definite amount, nevertheless, it will amount to a very considerable sum ...

This letter (or the first page of it, anyway) comes from the collection of ex-TAG Prez Tom Sito, who writes: "The legend is that in the early 1930s, when Walt Disney was watching other cartoons, he already had the planning of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" on his mind. He needed animators who could draw realistic women convincingly. "Walt saw a Betty Boop cartoon, and when Natwick's handling of the character passed before his eyes, he stood up in the theater and said 'We gotta get that guy!'" Which they did. A few years after this letter. (When Mr. Sito returns from his overseas mission, we will try to lay our hands on the second page of the above. Right now we have only page one -- which gives us most but not all of the pertinent info. But we post it here anyway.) Addendum: Be sure to read the comments for the context of this letter, and go to the ASIFA Animation Archive Blog to see the full letter (and tons of other fantastic stuff).

Click here to read entire postSunday, August 27, 2006

Weekend Animation Box Office -- The Slow Fade

Nothing but live-action releases at the tail end of summer, and animation continues to recede into the background...

Monday through Thursday totals show only one animated feature in the top ten. And that top ten player is "Barnyard," anchored at #6, closing in on a $50 million domestic gross...

"Monster House" sits at #14, having gathered in $68.2 million (and becoming an example of bad word of mouth for the L.A. Times -- see below.)

"The Ant Bully" hangs at #16 with a gross of $25 million. It's on 850 screens, but that total is bound to shrink...

Update One: "Barnyard" descends to #10, but crosses the fabled $50 million barrier.

Update Two: There are now four animated features in release, all of them on the downhill slopes of their respectrive runs...

"Barnyard" in 10th position, has now collected $54.7 million. "Monster House" comes in at 16th with a cume of $69.3 million. "Cars is down to 531 theatres and now grossing under a million (its total stands at $240,548,00 domestic.)

And lastly, the sill-born "Ant BUlly takes in $685,000 in the 22nd slot, for a take of $25,795,000.

Click here to read entire post

Nothing but live-action releases at the tail end of summer, and animation continues to recede into the background...

Monday through Thursday totals show only one animated feature in the top ten. And that top ten player is "Barnyard," anchored at #6, closing in on a $50 million domestic gross...

"Monster House" sits at #14, having gathered in $68.2 million (and becoming an example of bad word of mouth for the L.A. Times -- see below.)

"The Ant Bully" hangs at #16 with a gross of $25 million. It's on 850 screens, but that total is bound to shrink...

Update One: "Barnyard" descends to #10, but crosses the fabled $50 million barrier.

Update Two: There are now four animated features in release, all of them on the downhill slopes of their respectrive runs...

"Barnyard" in 10th position, has now collected $54.7 million. "Monster House" comes in at 16th with a cume of $69.3 million. "Cars is down to 531 theatres and now grossing under a million (its total stands at $240,548,00 domestic.)

And lastly, the sill-born "Ant BUlly takes in $685,000 in the 22nd slot, for a take of $25,795,000.

Click here to read entire post

The OTHER Walt

Now that Oswald the Lucky Rabbit has been returned to his original owners, it's good to remember that there was another Walter in town making animation...

Walter Lantz didn't rise to the same stratospheric heights as Mr. Disney, but he was around a whole lot longer, cranking out new shorts until 1972 (the Disney shorts unit, but contrast, closed in '58. And Warners Animation shut down in 1963.)

George "Nick" Nicholas remembers the studio thusly:

Now that Oswald the Lucky Rabbit has been returned to his original owners, it's good to remember that there was another Walter in town making animation...

Walter Lantz didn't rise to the same stratospheric heights as Mr. Disney, but he was around a whole lot longer, cranking out new shorts until 1972 (the Disney shorts unit, but contrast, closed in '58. And Warners Animation shut down in 1963.)

George "Nick" Nicholas remembers the studio thusly:

In the late 1930s Walt Lantz had his studio on the Universal lot. One day one of the cartoonists came in early and brought a cow-pie from the back lot. He put it under an animation board on top of the light bulb. As the day progressed, the smell increased. What started out to be a gag, turned out to be a disaster. It took a couple of days to air the room out. Another morning, the girls coming in were met by goldfish swimming around in the drinking water bottle. After some wild reactions, one of the fellows came over to take them out. The bottle slipped out of his hands...leaving water, broken glass and flappping goldfish everywhere.Click here to read entire post

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Disney Vignettes

Some more snippets of interviews I conducted two decades ago. This time, I focus on Disney old-timers (doesn't everybody?)...

First up, this reminiscence from Harry Holt:

Some more snippets of interviews I conducted two decades ago. This time, I focus on Disney old-timers (doesn't everybody?)...

First up, this reminiscence from Harry Holt:

When I started at Disney's Hyperion studio in 1936, animation was exploding and it was a young man's game. I was in the annex across the street from the main studio, and every time there was an addition build on -- a couple more rooms -- Walt would come racing across the street to check it out. Like others at that time, I came in and tried out for two weeks, illustrating several storylines, so they could see how you'd handle it. After a week and a half, they put me onto a short called "Woodland Cafe" as an in-betweener, and then I went on to "Snow White." I was Eric Larson's assistant for awhile. He was the father superior of the place, and everyone came to him with their problems.And this from Lee Blair...

Years ago at Disney, there was a comic strip artist who didn't have any sense of humor at all. Wasn't real friendly either. Every day a group of us would go across the street to a drug store for coffee and donuts, and this guy would stay in his room and eat a can of Del Monte's fruit cocktail. We were a little irritated that he wasn't more social, so one day we got the idea to go down the street and buy several cans of fruit cocktail, and some cans of corn, peas and string beans that were the same size. We put the fruit cocktail labels on the vegetable cans, and every three or four weeks we'd switch our phony fruit cocktail with one of this guy's real ones. Well, this guy was amazed that Del Monte could make a mistake like that. And after it happened to him twice, he decided to write Del Monte about it. He got a note back from Del Monte's president saying such a thing was impossible. We convinced him to write Ripley's "Believe it or Not," based in New York, which he did. One of the fellas knew Ripley and phoned him long distance about the joke, and told him to Special Deliver that letter back to him. Ripley did, and then we sealed a phony letter from Ripley into a can of fruit cocktail that said the whole thing was an elaborate joke. The guy read it and went out of his mind.And finally this from Ken O'Brien:

There was an amusing event that happened while "Alice In Wonderland was starting production. A group of us animators and assistants gathered in Milt Kahl's room with drawings we'd made of Alice. We would hand over our drawings to Milt {one of the best draftsmen in the history of animation} and he would work over them, point out ways to improve them. John Freeman handed over his drawing, an upshot angle of Alice's face, and as Milt worked over it, he wasn't happy with his first attempt and began another. As he worked he grunted: "This is a tough drawing to do!" to which Freeman deadpanned: "I didn't have any trouble with it." Everyone in the room, including Milt, broke up.Click here to read entire post

Large 401(k) Stashes

Let's veer away from animation momentarily and talk about 401(k) pension plans, and the people who own them. Many employees today participate in their company or union 401(k) plans, but many (most?) employees don't utilize them to the max, which is a shame.

Because individuals who've been tucking money into them for seven or ten years should have a nice pile of loot by now, as this L.A. TIMES article explains...

I've been enrolling animation employees in The Animation Guild's 401(k) Plan for a decade. TAG, through a simple twist of fate (in 1985 the animation guild was thrown out of the IATSE's contract bargaining unit with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers) found itself with the wherewithal and leverage to negotiate a 401(k) Plan with most of the major animation studios. (If we had NOT been thrown out of the bargaining unit, this couldn't have happened. I won't bore you with the details as to why.)

So here it is 11-plus years later, and a goodly number of TAG's members have a hundred thousand dollars (or more) in the TAG 401(k) Plan. This is on top of the fifty to a hundred grand most of them have in the Motion Picture Pension Plan's IAP (Individual Account Plan). I don't care how ferocious inflation might be, two hundred thousand dollars is a nice trunk-full of money on which to be sitting.

The questions I get asked about the most regarding TAG's 401(k) Plan are 1) Why should I enroll in it since TAG's Plan has no match? and 2) What should I invest in?

The first question is easy. Yes, you should enroll. It's a way of sheltering income and painlessly saving for retirement. (You should also utilize IRAs and Roth-IRAs.)

One thing I know about many animation employees is they live paycheck to paycheck no matter how much or little they're making, so peeling off a few bucks every week and tucking them away where you won't spend them is a fine idea. (Most 401(k) plans have a match, so the motivation is even stronger there. But it is still amazing how many people don't enroll.)

As to the second question, that's a bit more complex. But I have a single, one-word answer that I've used for years. That word is: "DIVERSIFY." If you have thirty years before you hang it up, you'll want to have a lot of different kinds of stock investments (foreign stocks, domestic stocks. Large company stocks, small and medium company stocks.) Also a little bit of bond exposure.

If you are close to retirement, then you'll want to be more heavily weighted in short-term and some medium-term bonds. But you'll still want stock exposure.

I'm not a financial advisor, but the esteemed Ric Edelman is, and Ric advises that people with fairly lengthy time horizons before retirement be 100% invested in stocks. Whether you buy this or not (I don't), Mr. Edelman is worth reading. His book "The Truth About Money" is a good place for anyone serious about saving for retirement to start. His prose is clear and entertaining, and although some of his conclusions and analyses are open to debate (see the reviews at the Amazon link above), he is right, I think, more than he's wrong.

My main point: If you're reading this and in a position to participate in a 401(k) plan, do so. Time speeds by, and you'll be sixty a lot quicker than you now think you'll be.

Click here to read entire post

Let's veer away from animation momentarily and talk about 401(k) pension plans, and the people who own them. Many employees today participate in their company or union 401(k) plans, but many (most?) employees don't utilize them to the max, which is a shame.

Because individuals who've been tucking money into them for seven or ten years should have a nice pile of loot by now, as this L.A. TIMES article explains...

I've been enrolling animation employees in The Animation Guild's 401(k) Plan for a decade. TAG, through a simple twist of fate (in 1985 the animation guild was thrown out of the IATSE's contract bargaining unit with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers) found itself with the wherewithal and leverage to negotiate a 401(k) Plan with most of the major animation studios. (If we had NOT been thrown out of the bargaining unit, this couldn't have happened. I won't bore you with the details as to why.)

So here it is 11-plus years later, and a goodly number of TAG's members have a hundred thousand dollars (or more) in the TAG 401(k) Plan. This is on top of the fifty to a hundred grand most of them have in the Motion Picture Pension Plan's IAP (Individual Account Plan). I don't care how ferocious inflation might be, two hundred thousand dollars is a nice trunk-full of money on which to be sitting.

The questions I get asked about the most regarding TAG's 401(k) Plan are 1) Why should I enroll in it since TAG's Plan has no match? and 2) What should I invest in?

The first question is easy. Yes, you should enroll. It's a way of sheltering income and painlessly saving for retirement. (You should also utilize IRAs and Roth-IRAs.)

One thing I know about many animation employees is they live paycheck to paycheck no matter how much or little they're making, so peeling off a few bucks every week and tucking them away where you won't spend them is a fine idea. (Most 401(k) plans have a match, so the motivation is even stronger there. But it is still amazing how many people don't enroll.)

As to the second question, that's a bit more complex. But I have a single, one-word answer that I've used for years. That word is: "DIVERSIFY." If you have thirty years before you hang it up, you'll want to have a lot of different kinds of stock investments (foreign stocks, domestic stocks. Large company stocks, small and medium company stocks.) Also a little bit of bond exposure.

If you are close to retirement, then you'll want to be more heavily weighted in short-term and some medium-term bonds. But you'll still want stock exposure.

I'm not a financial advisor, but the esteemed Ric Edelman is, and Ric advises that people with fairly lengthy time horizons before retirement be 100% invested in stocks. Whether you buy this or not (I don't), Mr. Edelman is worth reading. His book "The Truth About Money" is a good place for anyone serious about saving for retirement to start. His prose is clear and entertaining, and although some of his conclusions and analyses are open to debate (see the reviews at the Amazon link above), he is right, I think, more than he's wrong.

My main point: If you're reading this and in a position to participate in a 401(k) plan, do so. Time speeds by, and you'll be sixty a lot quicker than you now think you'll be.

Click here to read entire post

Friday, August 25, 2006

Friday Studios

I usually attempt to stay around the office more on Fridays, but that didn't happen today, as I hopped down to Wilshire Blvd. to visit the crews on "Family Guy" and "American Dad" at Fox Animation...

It was lucky that I drove down in the morning, since 80% of the staff was leaving at noon for the Lake Malibu Club high in the hills above Agoura. The studio, it seems, was throwing a Friday afternoon picnic and spirits were high. And I would have been depressed if I'd blown an hour in the car getting to the studio, then found most everyone gone to Lake Malibu.

Back in the Valley, I ended up at a disciplinary meeting for a young artist (one of my favorite activities.) The supervisor had issues with the guy's work, and so wrote him up with the usual boiler plate ("If your work fails to improve, further disiplinary action may be taken, up to and including discharge.")

The artist, understandably, wasn't happy about it. My advice was to seek some accomodation and a truce with the boss, because one thing I know from long observation and my own stupid moves in story departments: it doesn't help to get into a test-of-wills thing with the guy in charge. You almost always end up at the fuzzy end of the popsicle stick.

This only took me fourteen years to learn. I'm not a quick study.

Click here to read entire post

I usually attempt to stay around the office more on Fridays, but that didn't happen today, as I hopped down to Wilshire Blvd. to visit the crews on "Family Guy" and "American Dad" at Fox Animation...

It was lucky that I drove down in the morning, since 80% of the staff was leaving at noon for the Lake Malibu Club high in the hills above Agoura. The studio, it seems, was throwing a Friday afternoon picnic and spirits were high. And I would have been depressed if I'd blown an hour in the car getting to the studio, then found most everyone gone to Lake Malibu.

Back in the Valley, I ended up at a disciplinary meeting for a young artist (one of my favorite activities.) The supervisor had issues with the guy's work, and so wrote him up with the usual boiler plate ("If your work fails to improve, further disiplinary action may be taken, up to and including discharge.")

The artist, understandably, wasn't happy about it. My advice was to seek some accomodation and a truce with the boss, because one thing I know from long observation and my own stupid moves in story departments: it doesn't help to get into a test-of-wills thing with the guy in charge. You almost always end up at the fuzzy end of the popsicle stick.

This only took me fourteen years to learn. I'm not a quick study.

Click here to read entire post

A Salute To Our Men in Uniform -- The Fort Monmouth gang

Above: Chuck McKimson, Lew Irwin, Bob Givens, Irv Spector (kneeling), Leon Schlesinger, Capt. Smith, Sid Katz.

Here's a group of animation artists serving Uncle Sam back east (in New Jersey, not Iraq, and during WWII, not our current war.) Chuck McKimson was one of the animation pillars at Warner Bros. Animation for years and years...Lew Irwin, who had a long career in animation as both animator and assistant...Bob Givens, longtime layout tyro at Warner Bros. Animation...animator Irv Spector ...Leon Schlesinger (the owner/operator of Termite Terrace before he sold out to WB. Here he's wearing what looks like a VFW cap, so I'm assuming Leon was a WWI vet)...and animator Sid Katz. These men in uniform were working in the motion picture unit at Fort Monmouth. Another well-known unit was "Fort Roach" in Culver City, California. Click here to read entire postWord of mouth

This article in today's Los Angeles Times is worth perusing. It's on the buzz that some films get, and some films don't...

This paragraph regarding Monster House is telling:

This article in today's Los Angeles Times is worth perusing. It's on the buzz that some films get, and some films don't...

This paragraph regarding Monster House is telling:

The wrong kind of word of mouth can be devastating. When Sony released Monster House earlier this summer, the animated movie collected some of the season's best reviews and opened to a respectable $22.2 million. But in its second weekend, the film slipped nearly 48%. Sony believes the sharp drop-off was largely attributable to parents' telling other parents that Monster House was too intesne for small children. Thanks to that don't-dare-take-your-six-year-old advice, the film collapsed more than 40% the next three weekends, and was soon history.A friend of mine thought that Monster House would have been better released around Halloween, but maybe Moms wouldn't have taken the kiddies in October either... Click here to read entire post

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Thursday 'Toon Walkarounds

I continued my blistering pace on Thursday, visiting Nickelodeon's Studio in Burbank and Disney Toons and Disney TVA in the Frank Wells Building...

Over at Nick, a number of artists are going "on hiatus" (sometimes referred to as "layoff") as the suits decide when Nick starts production on Butch Hartman's new show "Splatypus." It sort of looks like a number of Nickelodeon employees -- some with long, unbroken tenures -- will be receiving their walking papers until Splatypus revs up in October.

At Disney Toons, the first CGI animators have been hired to work on "Tinkerbelle," the next entry in the "Peter Pan" franchise. We're informed that most of the animation will be done on the Indian subcontinent, but that a crew of ten or eleven animators will form a second unit in Burbank.

I continued my blistering pace on Thursday, visiting Nickelodeon's Studio in Burbank and Disney Toons and Disney TVA in the Frank Wells Building...

Over at Nick, a number of artists are going "on hiatus" (sometimes referred to as "layoff") as the suits decide when Nick starts production on Butch Hartman's new show "Splatypus." It sort of looks like a number of Nickelodeon employees -- some with long, unbroken tenures -- will be receiving their walking papers until Splatypus revs up in October.

At Disney Toons, the first CGI animators have been hired to work on "Tinkerbelle," the next entry in the "Peter Pan" franchise. We're informed that most of the animation will be done on the Indian subcontinent, but that a crew of ten or eleven animators will form a second unit in Burbank.

Preproduction on the new CGI "Winnie the Pooh" series (with a GIRL?!) is winding its way to completion. The last production boards on the show's initial order should be wrapped in November.

Click here to read entire post

Preproduction on the new CGI "Winnie the Pooh" series (with a GIRL?!) is winding its way to completion. The last production boards on the show's initial order should be wrapped in November.

Click here to read entire post

Snippets of History -- Termite Terrace

Let's get away from Disney and DreamWorks for a moment, and shuffle backward in time to Termite Terrace -- the animation studio in Hollywood that was owned and operated by Leon Schlesinger and then by the Brothers Warner...

I collected these first-person accounts twenty years ago for an Animation Guild awards book; generous soul that I am, I share them with you now...

Let's get away from Disney and DreamWorks for a moment, and shuffle backward in time to Termite Terrace -- the animation studio in Hollywood that was owned and operated by Leon Schlesinger and then by the Brothers Warner...

I collected these first-person accounts twenty years ago for an Animation Guild awards book; generous soul that I am, I share them with you now...

Back in the 'thirties Leon Schlesinger had his cartoon unit for Warner Brothers cartoon in a two-story building on Van Ness. Storymen downstairs, animators and assistants upstairs. Every day the food wagon would come by and everyone would yell out their orders and send down their money in a basket. The trouble was that half the time the storymen downstairs would take the sandwiches out of the basket on the return trip. And lots of days, the last half-hour before quitting time the guys would crumple up animation paper and get into paper fights. By the time we left, the place would be ankle deep in balls of animation paper.

Left: outside the Schlesinger studio in the summer of 1941. And why are so many people on the sidewalk? Because Leon has just locked them out for supporting the Screen Cartoonists Guild in what Chuck Jones called "our little six-day war."

There were always lots of activities going on at Schlesinger. Every day we would run out on our coffee breaks and put down our nickels to play "showdown poker." Directors like Tex Avery started playing and betting a lot of money. Well, their wives got wind of it and called the cops, who came in and raided the place.

A DreamWorks Afternoon

DreamWorks is a studio in which it's easy to while away an afternoon. (Fountains, canals, lagoons...)

I talked to a LOT of artists. In fact I spent more time in more rooms in more comofrtable chairs than I have in months (usually I'm breezing in and out of doors, trying to cover as much territory as possible).

A decade ago I relearned a central rule of every animation studio (which I'll repeat for the tenth time.) No matter how wonderful or horrible a company's work environment, there are always three groups inside of it: the disgruntled, the halfway contented, and the outright happy. If the studio is a grim sweatshop, you still have the three groups, but the Disgruntled make up the largest demographic. And a well-run, relaxed operation STILL gives you the three groups, except now the Happy Artists predominate.

I certainly found the three groups in evidence at DreamWorks on Wednesday. I came across an unhappy artist (he'd had a lot of his work left on the cutting room floor because of story changes and was stewing about it), the director whose picture is going "really well" (we talked about actors at recording sessions, and how the Brits have a real hard-edged work ethic: they come in prepared, and are willing to try anything.)

And there was the story artist who was excited about the new project he'd just started, but a little nervous about how the project was going to turn out. (Chalk him up as "reasonably content.")

I don't think I realized until today that DW probably has a bigger slate of feature films on its calendar than any other studio in town. There is "Flushed Away," coming this Fall. "Shrek III" rolls into your neighborhood AMC during Spring of '07, then there's "Madagascar II" (with, I'm told, a more satisfyingly symmetrical storyline than Madagascar I") and "Bee Movie" and "Kung Fu Panda" out there in 2008, 2009.

Beyond all those, there are two more features in the early stages of development, but since the studio hasn't settled on their titles, let alone announced them, there's no point in me pounding away on my keyboard about them.

Click here to read entire post

DreamWorks is a studio in which it's easy to while away an afternoon. (Fountains, canals, lagoons...)

I talked to a LOT of artists. In fact I spent more time in more rooms in more comofrtable chairs than I have in months (usually I'm breezing in and out of doors, trying to cover as much territory as possible).

A decade ago I relearned a central rule of every animation studio (which I'll repeat for the tenth time.) No matter how wonderful or horrible a company's work environment, there are always three groups inside of it: the disgruntled, the halfway contented, and the outright happy. If the studio is a grim sweatshop, you still have the three groups, but the Disgruntled make up the largest demographic. And a well-run, relaxed operation STILL gives you the three groups, except now the Happy Artists predominate.

I certainly found the three groups in evidence at DreamWorks on Wednesday. I came across an unhappy artist (he'd had a lot of his work left on the cutting room floor because of story changes and was stewing about it), the director whose picture is going "really well" (we talked about actors at recording sessions, and how the Brits have a real hard-edged work ethic: they come in prepared, and are willing to try anything.)

And there was the story artist who was excited about the new project he'd just started, but a little nervous about how the project was going to turn out. (Chalk him up as "reasonably content.")

I don't think I realized until today that DW probably has a bigger slate of feature films on its calendar than any other studio in town. There is "Flushed Away," coming this Fall. "Shrek III" rolls into your neighborhood AMC during Spring of '07, then there's "Madagascar II" (with, I'm told, a more satisfyingly symmetrical storyline than Madagascar I") and "Bee Movie" and "Kung Fu Panda" out there in 2008, 2009.

Beyond all those, there are two more features in the early stages of development, but since the studio hasn't settled on their titles, let alone announced them, there's no point in me pounding away on my keyboard about them.

Click here to read entire post

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

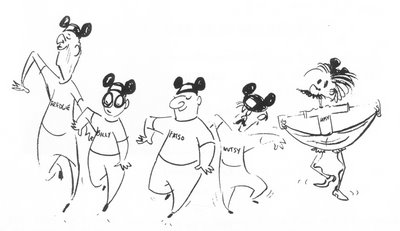

The Animation Mouseketeers

Here are Freddie, Billy, Fatso, Nutsy and Tipsy ...

or as they were better known, Fred Kopietz, Bill Southwood, Ed Solomon, Lou Appet* and George "Nick" Nicholas. Disney, circa 1955.

1955 was a pivotal year for Disney. The studio was still making shorts, still making animated features, and the year before it had shot its first big budget live-action feature "20,000 Leagues under the Sea." It had plunged into television with the prime time "Disneyland" and the late-afternoon "Mickey Mouse Club."

And Walt had once again rolled the dice, sinking the studio assets into a few hundred acres of orange groves in Anaheim, California. For an amusement park that had more in common with Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, Denmark than it did with Coney Island, New York.

1955. Definitely a make-or-break milestone in the long history of the Mouse House.

* Lou was a layout artist who was active in the Fleischer strike in New York, and forty years later was the President and then the Business Representative of The Animation Guild (then the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists) in Los Angeles.

Click here to read entire post

Here are Freddie, Billy, Fatso, Nutsy and Tipsy ...

or as they were better known, Fred Kopietz, Bill Southwood, Ed Solomon, Lou Appet* and George "Nick" Nicholas. Disney, circa 1955.

1955 was a pivotal year for Disney. The studio was still making shorts, still making animated features, and the year before it had shot its first big budget live-action feature "20,000 Leagues under the Sea." It had plunged into television with the prime time "Disneyland" and the late-afternoon "Mickey Mouse Club."