I remember when I first went to work at Disney, cycle animation was kind of a no-no. If you used a cycle you shouldn’t make your audience aware of it. But you have to realize that when people started to animate, in the old days it was such a difficult process that they looked for simple or almost abstract ways of drawing characters, because the very basic nature of it was multiple drawings which were time-consuming to do. So you invented characters that were on the round side, because everybody knows that it’s faster to do anything if you roll and turn and spiral instead of going in straight lines, or cutting corners, or turning corners.

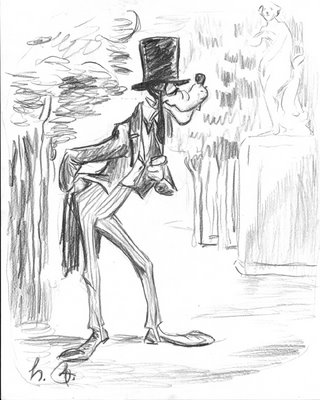

So your characters became very simple, almost abstract. And when you analyze Mickey Mouse he was two circles connected with two lines, and we had what we call rubber hose animation because Mickey’s and Minnie’s legs both look like black rubber hoses and they acted like sort of a whipping action.

But as we got into more realistic approaches, beginning with the little fairy and the flying mouse…those were the beginnings and you learned how difficult they were. And with Snow White, with the queen they used rotoscope for starters, rotoscoping a villain from a play called “The Drunkard” as sort of inspiration for the witch, but we never did trace them like we did Snow White. There we actually went over [the girl] with rotoscope prints. We changed the head and the proportions ...

So as animation became more of a movie illustration, we got away from that rubber hose arbitrary way of drawing ... The funny thing is, when you look at Winsor McCay’s animation it’s so startlingly real. The thing he did with the mosquito landing on this guy’s forehead was a beautiful drawing of a mosquito, but yet it has sort of a humorous charm about it. Well, he drew exactly like he did his "Little Nemo" strip, which was super illustration, a bit of color like a comic book, but McCay was a realist and didn’t follow the rest of the cartoonists.

The demand [in early animation] was that you had to draw like a comic strip character -- like Felix on the screen -- to be funny. And if you did it realistically you could not be funny. [Early cartoons] were just a series of one gag after another, so in order to make them funny you had to have gross characters done sometimes in an obscene amount of exaggeration. And then we got into more believable stories and plots, like Snow White, and personality development of those seven dwarfs, each one of them different, compared to the early Mickeys where everybody just bounced and played instruments.

SH: Talk about Fred Moore.

WK: Fred deviated from the rubber hose, round circle school. Fred was just right for the time. He was the first one to escape from the rubber hose school. He began getting counter movements, counter thrusts, in the way he drew. More drawing. He decided to make Mickey’s cheeks move with his mouth, which had never been done before when you drew everything inside that circle. He squashed and stretched him more.

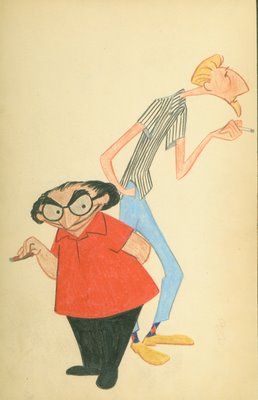

And this was right at the time, but Fred was a high school-trained animator. He never went to art school, and he more or less emerged drawing that way. Nobody seems to remember any development. It just came there and started, but the interesting thing is he never went beyond that part. The rest of us came into that place. It was a strange place, we adapted to it and we kept trying to improve and change, and we became students of it. Milt Kahl, myself, Frank and Ollie. We knew it was a tough art, and there were many nuances of techniques and conceptions regarding the way you drew, and the thing we saw was that there were millions of things of things to be learned yet and to try.

Fred never thought of that. He wasn’t a student of animation, he was just a naturally gifted animator whose style and development was perfect, timing-wise, for that point of time of where the studio wanted to go. And when the studio kept going in that direction it became the students, the guys I named, who carried it on. And Fred, being the type of character he was, almost juvenile in a way, was not able to cope with this. He took to drinking instead of saying “Gee, this is interesting. I’ll sit down and explore it too, and improve and rise above what I’ve done.”

The idea was to try to do better than you did the year before, because it was such an open thing. We were pioneering techniques in animation styles that had never been done before. But Fred was content to stay at this one level, and he got all his adulation for The Three Pigs. Pigs isn’t bad. It’s wonderful for the time. It made everything that came before look very crude, and it gave the studio the shot in the arm that Walt thought was wonderful.

So Fred was the man of the hour and couldn’t handle it, really, if you want to know. He just expected to be the man of the hour forever, and then we began to notice that as we got more into the subtleties of animation, slowing in and out, and the little nuances which were not banging and jumping around all the time, Fred’s work began to look crude.

Now that’s a hell of a thing to say, but I’m talking relatively speaking. I noticed it on The Reluctant Dragon. Fred was given the knight with the little boy, and what had been the acceptable way on The Three Little Pigs and in some cases Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, there were parts, even though they were drawn well, that were crude, timing-wise.

Fred would hit a pose and just freeze there and while we were already loosening those things up and putting in the subtle things that would keep [the animation] alive a long time. That’s what I meant, that at that time Fred was drinking heavily, and I was secretly going in with his exposure sheets and adding these other little drawings that would make them work with the rest of the animation that was being done on the picture.

And more and more, Fred became defensive, and hitting the bottle and feeling sorry for himself. He’d come back from lunch and would want to talk about it, and of course we didn’t want to talk about it. And he wanted to talk about it every afternoon, how the place was giving him a bad deal, and all that, and Walt wasn’t good to him any more.

We just felt sorry for him. We didn’t know what to do and all of a sudden ... you know his brother and father, they had the same drinking problem. We didn’t know that. We’d all go out and have a martini, and with Fred it would become an obsession. And it became an escape when he couldn’t handle the situation in the studio.